ORIGINS OF GIN

It is claimed that British soldiers who provided support in Antwerp against the Spanish in 1585, during the Eighty Years' War, were already drinking genever (the juniper-flavored liquor from which gin evolved) for its calming effects before battle, from which the term “Dutch Courage” is believed to have originated.

It's no coincidence that Dutch physician, Franciscus Sylvius has been credited with the invention of gin and by the mid 17th century, numerous small Dutch and Flemish distillers had popularized the re-distillation of malt spirit or malt wine with such herbaceous additions as juniper, anise, caraway, coriander and the like, which were then sold in pharmacies and used to treat such medical problems as kidney and stomach ailments, lumbago, gallstones and even gout!

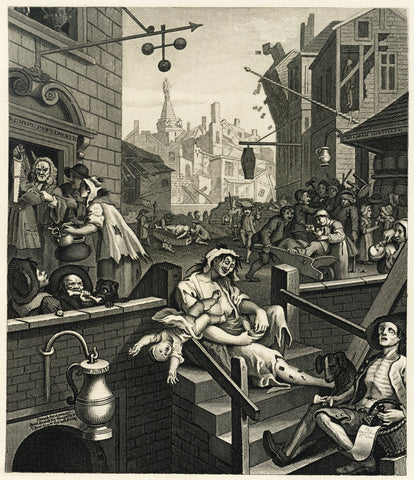

By the mid 18th century, due to the British government’s allowance of unlicensed gin production—as well as an imposed heavy duty on all imported spirits—gin drinking in England had risen significantly. However, the scenario created a market for poor-quality grain that was unfit for brewing beer and in turn, thousands of gin shops sprang up throughout the country, a period known as the “Gin Craze.” Because of the relative price of gin (when compared with other drinks available at the time and in the same geographic location), gin began to be consumed regularly by the poor. Of the 15,000 drinking establishments in London at the time (not including coffee shops and drinking-chocolate shops) over half were gin shops! Blimey!

TONIC

In herbal medicine, an herbal tonic (a solution or other preparation made from a specially selected assortment of herbs) is used to help restore, tone and invigorate systems in the body or to promote general health and well-being. (I’ll drink to that!)

Quinine is a natural white crystalline alkaloid having fever-reducing, pain-killing and anti-inflammatory properties, along with a bitter taste. The bitter-tasting agent was the first effective Western treatment for malaria, appearing in therapeutics in the 17th century and is currently on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines—a list of the most important medications needed in a basic health system.

Quinine occurs naturally in the bark of the cinchona tree. Its medicinal properties were first discovered by the indigenous peoples of Peru who would mix the ground bark with sweetened water to offset its bitter taste, thus producing tonic water. Because quinine powder was so unpalatable to the British officials stationed in early 19th century India and other tropical posts, they began mixing the quinine powder (added as a prophylactic against malaria) with soda and sugar—thereby creating a basic tonic water—to mask its bitter flavor.

Medicinal tonic water originally contained only carbonated water and a large amount of quinine. Compared to the first commercially-produced tonic water in 1858, most modern-day tonic water contains a less significant amount of quinine and is thus used primarily for its flavor. Consequently, it’s less bitter and usually sweetened (often with high-fructose corn syrup or sugar). Premium tonic water brands such as Tomr's Tonic, Fever-Tree and Q Tonic have thus entered the marketplace, emphasizing the use of real quinine and natural sweeteners, as opposed to quinine flavoring and high-fructose corn syrup. And, although less common, there is also traditional-style tonic water, containing little more than quinine and carbonated water for those who desire its characteristic bitter taste.

GIN & TONIC

A gin and tonic is a highball cocktail made with gin and tonic water poured over ice. The cocktail was introduced in the early 19th century by the army of the British East India Company in India, where malaria was a persistent problem. British officers took to adding a mixture of soda, sugar, lime and gin to the quinine in order to make the drink more palatable; soldiers were already given a gin ration and the sweet concoction made sense.

A gin and tonic is usually garnished with a wedge or slice of lime. In most parts of the world lime remains the only usual garnish; however, in the United Kingdom, it is not uncommon to use lemon as an alternative fruit. Use of both fruits together is known as an Evans. Although the origins of the use of lemons are unknown, their use dates back at least as far as the late 1930s. The use of either fruit is a hotly debated issue and while many gin brands recommend the use of lime, other industry experts such as the Master Distiller of Beefeater and the founder of Fever-Tree Tonic Water prefer lemon (although there are some that garnish a Beefeater-based gin and tonic with a slice of orange to complement the Seville orange Beefeater uses in its botanicals).

GIN-TONIC

In Spain, a variation on the drink called Gin-Tonic has become popular. This differs from a traditional gin and tonic as it is served in a balloon glass or coupe glass with plenty of ice and a garnish tailored to the flavors of the gin. The drink could be fruit-based, but the use of herbs and vegetables—reflecting the gin's botanicals—are increasingly popular. The balloon glass is used because the aromas of the drink can gather at its opening, therefore allowing the fragrance to be appreciated more readily.

THE MARTINI

The Martini is a cocktail made with gin and vermouth, and garnished with an olive or a lemon twist; a perfect martini uses equal amounts of dry and sweet vermouth, while a dry martini (which, during the Roaring Twenties, had become fashionable for people to ask for) uses dry white vermouth alone. By 1922, the Martini reached its most recognizable form in which London dry gin and dry vermouth are combined at a ratio of 2:1; stirred in a mixing glass with ice cubes, with the optional addition of orange or aromatic bitters; then strained into a chilled cocktail glass.

Over the course of the century the amount of vermouth steadily dropped. During the 1930s, the ratio was 3:1 and during the 40s: 4:1. In the latter part of the 20th century, 6:1, 8:1, 12:1, or even 50:1 or 100:1 martinis became considered the norm. And some martinis were made by filling a cocktail glass with gin, then rubbing a finger of vermouth along the rim. There are those who advocated the elimination of vermouth altogether: according to Noël Coward, A perfect martini should be made by filling a glass with gin, then waving it in the general direction of Italy (Italy being a major producer of vermouth).

Hence, there are several variations of the traditional “Martini.” The fictional spy, James Bond sometimes asked for his vodka martinis to be "shaken, not stirred," following Harry Craddock's The Savoy Cocktail Book (1930), which prescribes shaking for all its martini recipes (the proper name for a shaken martini is a Bradford). However, Somerset Maugham is often quoted as saying that "a martini should always be stirred, not shaken, so that the molecules lie sensuously on top of one another" (I’m certainly one with this school of thought!). And alternatively, a martini may also be served on the rocks, that is, with the ingredients poured over ice and served in an Old-Fashioned glass.

ORIGIN OF THE MARTINI

While during Prohibition, the relative ease of illegal gin manufacture led to the Martini's rise as the predominant cocktail of the mid 20th century in the U.S., the exact origin of the Martini is arguably “unclear.” Numerous cocktails with ingredients and names similar to the modern-day martini were first seen in bartending guides of the late 19th century. For example, in the 1888 Bartenders' Manual, there’s a recipe for a drink that consists in part of half a wine glass of Old Tom Gin and half a wine glass of vermouth. Then there’s the Marguerite Cocktail, which could very well be construed as an early form of the Martini, consisting as it did of a 2:1 mix of Plymouth dry gin and dry vermouth (with a dash of orange bitters). Yet in 1863, an Italian vermouth maker started marketing its product under the brand name, Martini which could very well have been the source for the cocktail's name.

Moreover is the theory suggesting that the Martini’s name evolved from a cocktail called the Martinez, served sometime in the early 1860s at the Occidental Hotel in San Francisco, which people frequented before taking an evening ferry to the nearby town of Martinez. Alternatively, the people of Martinez say the drink was first created by a bartender in their town, or that maybe it was named after the town. Then there’s the theory that links the first (dry) martini to the name of a bartender who concocted the drink at the Knickerbocker Hotel in New York City, circa 1910! It’s enough to make your head spin (if the 100:1 martini didn’t already)!

Note: Wikipedia-sourced references are paraphrased.